A home for the homeless from Hackney Cottage Homes to Great Stony School by Ron Barnes, Headteacher of Great Stony School from 1964 to 1988.

Introduction

During the Elizabethan period, each parish assumed responsibility for their own poor by provision of outdoor relief. The increasing demands of poor relief necessitated the 1834 poor law amendment act which led to the building of many workhouses, in which all ages were confined. The children in these institutions were vulnerable to sexual abuse and were subjected to other forms of immorality by the adult paupers. Many workhouses became ‘dens of iniquity’ and were overfilled with the illiterate poor.

Subsequent reforms led to the removal of children from workhouses and their placement in large ‘industrial schools’ later in the 19th century. It had become clear that these children were likely to end up in the adult workhouses unless some provision was made for their training. The size of these industrial schools (often 100 or more, with only two officers to look after them) meant that they had little in the way of home comforts. Boards of guardians made attempts to find foster homes and other smaller homes in their areas. In the metropolis this proved difficult, and guardians often looked for placements outside the urban area. One such was the Hackney board of guardians which is the subject of this study.

The size of the problem

In 1899 a meeting at the Hackney board of guardians expressed concern about the size of families especially amongst the poorer sections of the community. Families with a dozen or 15 (or sometimes more) children were often unable to feed or clothe them all, and it was not unusual for the older children to be turned out of the home to fend for themselves. These children had to be picked up off the streets and taken to a ‘pound’, before being returned to the board of guardians responsible for the area that they had come from. Hackney was dealing with two or three hundred children at any time, herded into industrial schools.

We will have to build but where?

The school committee report of the guardians on 16th of March 1900 showed that it was urgently considering the need for additional accommodation for children who were the responsibility of the guardians, as well for their maintenance and education. Three months earlier, the committee had agreed to engage Mr W Bramham as surveyor to assist in the search for a suitable site for a new children's home.

Into the new century

The Hackney board of guardians (covering the vestries of Hackney and Stoke Newington, with South Hornsey parish as a later addition) already had a school for pauper children in Brentwood, a workhouse like building known as the ‘Barrack’. This was inadequate by 1899, and in 1901, due to overcrowding, its quota was reduced to 446 children. The problem was aggravated by legislation in 1889 and 1899 which obliged guardians to take into care children of ‘dissolute parents’, as well as younger children about to be turned out by their families. All this was in addition to the normal responsibilities towards proper children in the workhouse, orphans and foundlings. The guardians tried in vain to find foster homes for the increasing number of children in their care.

By 1901 the total number of children in Hackney's care had risen to 826. A number of empty houses in Sydney St, Hackney Wick, were taken over and organised as cottage homes, mainly for younger children. Two years search had failed to find a suitable site for a new home in London, or to find suitable foster parents willing to work long hours on their own bringing up children. The ‘Sheffield scheme’ had been considered. This involved placing children in scattered foster homes around a fairly large neighbourhood. The children would have attended normal schools, and there would have been a small purpose-built centre containing an Infirmary and temporary hostel. Hackney favoured this scheme but was unable to implement it due to the shortage of foster parents, and the lack of a suitable site in Hackney on which to build the centre.

As a result of these difficulties Hackney sought places in Brentwood and the surrounding villages. It appears to be particularly successful in Ongar. Foster parents were paid and, initially, inspected by board officials at regular intervals. Unfortunately, ‘out of sight, out of mind’ the latter duty fell into abeyance. An inspection of foster homes in the summer of 1900 showed that all was not well. A motion to stop such visits on the grounds that they infringed the foster parent’s privacy, was rejected by the chairman and the guardians nominated four members to follow the matter up. Their report showed that the foster homes left a lot to be desired with children poorly clothed and infested with head lice. This made members more determined to build their own home.

Where to build

Mr Bramham and his team examined 21 sites, eventually reducing Mr 10 possible ones to be considered by the guardians. Three were at Pilgrim’s Hatch, two in Ongar and one each at Warley, Beacon Hill, Kelvedon Common, Theydon Bois, and Westwood Park in Brentwood. Members of the board visited all these sites, though the ones at Theydon and Westwood Park were viewed while passing in the train! A shortlist of three was produced - Pilgrims Hatch, Warley and one of the Ongar sites. After consideration, it was unanimously agreed that the Ongar site was by far the most suitable on the following grounds.

Position: the site was considered to be in excellent position, with good views and suitable for building in a healthy neighbourhood near to a Great Eastern railway station, and eight miles from the board's other home in Brentwood.

Frontage: 1,150 ft frontage to the London Road, and 1500 ft frontage to the Chelmsford Road.

Facilities: gas was available at 3s 3D per 1000 cubic ft, water at 1s 6d per 1000 gallons and the local authority was willing to seek approval from the Local Government Board to install a sewage system.

Local community: over the years the board had successfully found foster homes for many of the children in their care in the local area.

Altitude and contour: A clay soil freely intermixed with pebbles. The highest point was 212 feet, the lowest 180 feet. The approximate site area was 40 acres with an asking price of £200 per acre.

Concerns: the vendors maintained that there had been a plan in 1898 to build a light railway through part of the site. Inspection of the plans, however, showed that it would only touch the site at one corner, and would not interfere with the guardian’s intentions. The vendors were not happy with the boards wish to fence the whole site, particularly with an unclimbable fence, and it was agreed to strike out the word ‘unclimbable’. In spite of this, the final fence was topped with two strands of barbed wire.

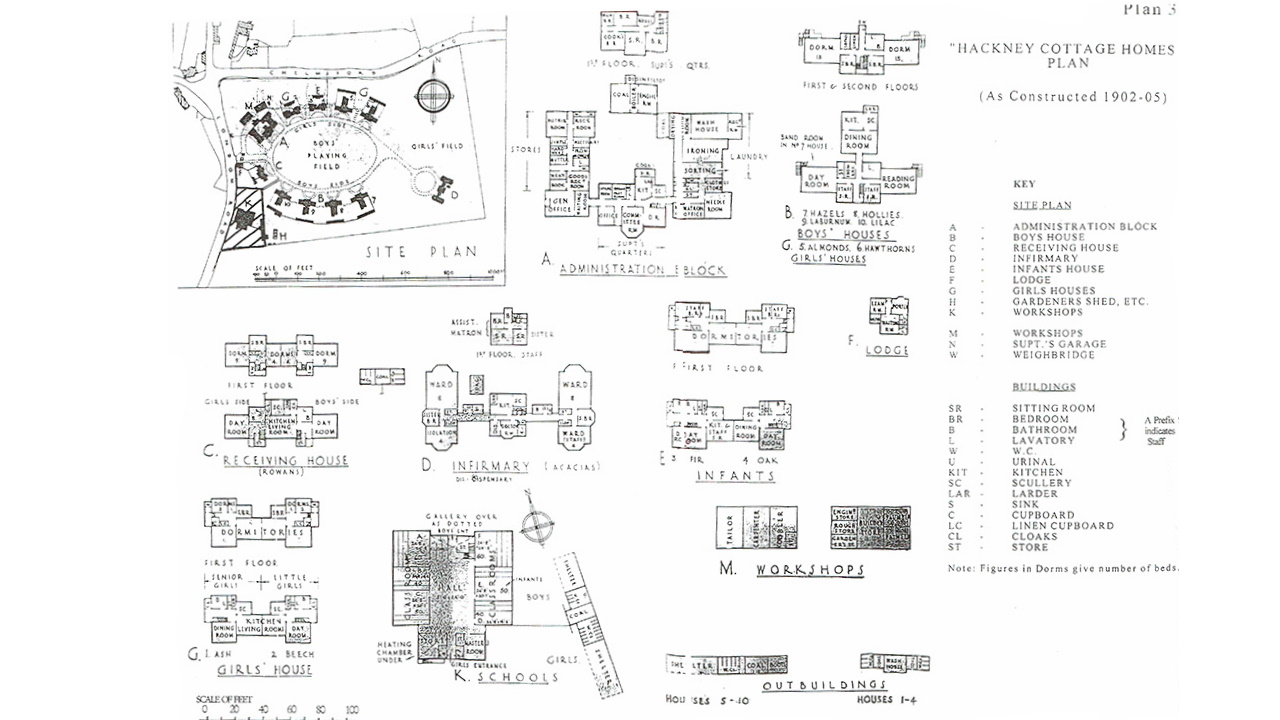

The purchase was agreed and finalised, with the tenant farmer, Mr Pratt being permitted to crop the land until the end of his tenancy. He would be compensated for any crop damage. In November 1902, the guardians received the estimated costs of building the homes: 994,000 cubic feet of building at ninepence half penny a foot - £39,345 16s, 8d; cost of work and drainage - £1200; engineering works to laundry - £300; building walls and fences - £700; digging, karting, levelling and road making - £1300. This totalled £42,845 16s and 8d. There were additional costs of: furnishing - £2,600; architects fee - £2,142; quantity surveyor’s fee - £550; clerk of works – £200; cost of raising loan - £50; contingencies - £612 3s and 4d, making a grand total of £49,000. In the New Year of 1903, it was agreed that the guardians could borrow the whole sum, of which £4,400 was to be paid back in 15 years and the remainder in 30 years.

Schooling and church attendance

The original intention was for the children to go to school in the town. In February 1903, the board met the Rev. Tanner and three other members of the Joseph king trust to discuss a plan to allow the guardians to extend the kings trust school in order to accommodate a large number of extra children from the home. In due course this offer was declined because of the difficulties that it would have caused the trust. The guardians were therefore obliged to plan and build school buildings on its own site, but these could not be completed before the homes were ready. Children would have to receive their instruction in their cottages until the new school was finished. Agreement was also reached at this time for children to attend whichever local church corresponded with their parents’ religious denomination. In June 1903 the guardians as the new landowner, received a request for £188 4s 7d in respect of the Ongar tithe rent.

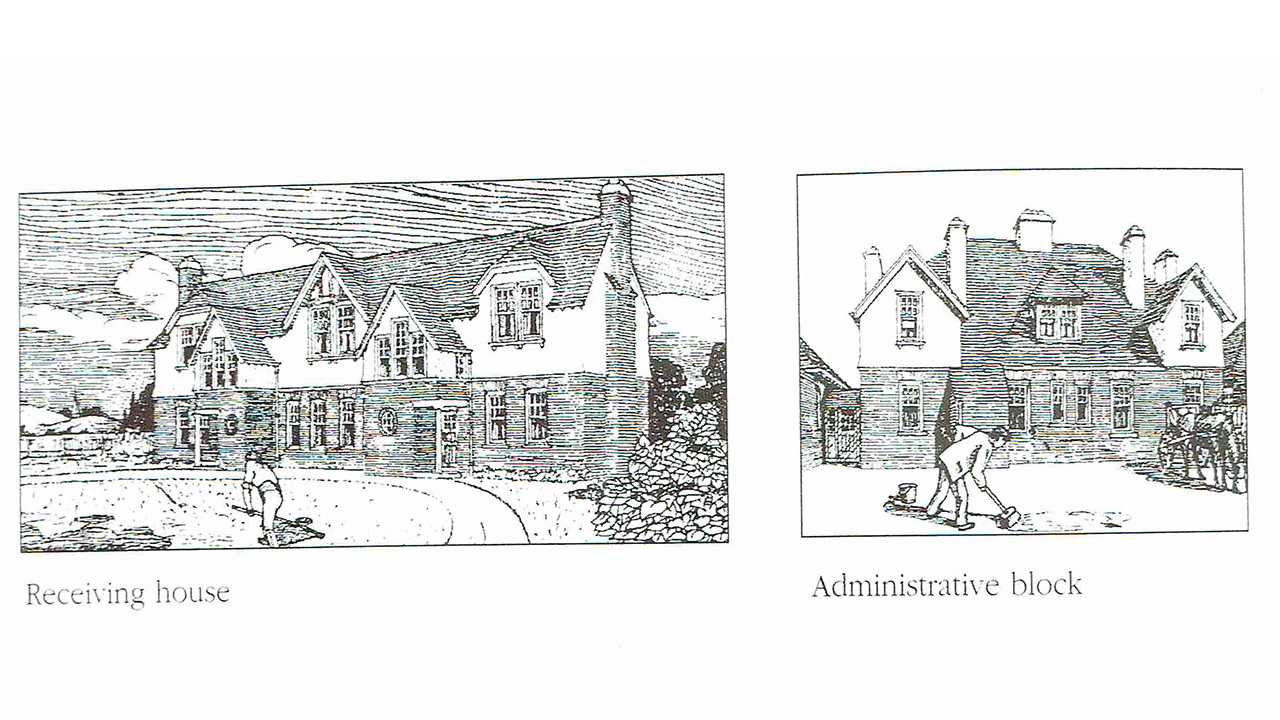

The building of the Ongar Cottage Homes

Having received revised drawings for the administration block, specifications were sent out to 32 different firms for estimates. These tenders were opened on the 29th of July in 1903 and range from £59,835 to £47,987. The lowest was from McCormick and Sons, of Northampton St, Essex Rd, London. The guardians were delighted that the lowest tender was within their estimated costs. However, one member proposed an amendment that consideration of the tenders should be delayed for six months, and this amendment was seconded and carried. Upset by this delay, another member sent the chairman a notice of a motion to rescind this decision. An extraordinary meeting of the board was duly held in August 1903, the previously amended motion was put to the meeting and defeated, and Messrs McCormick asked to go ahead.

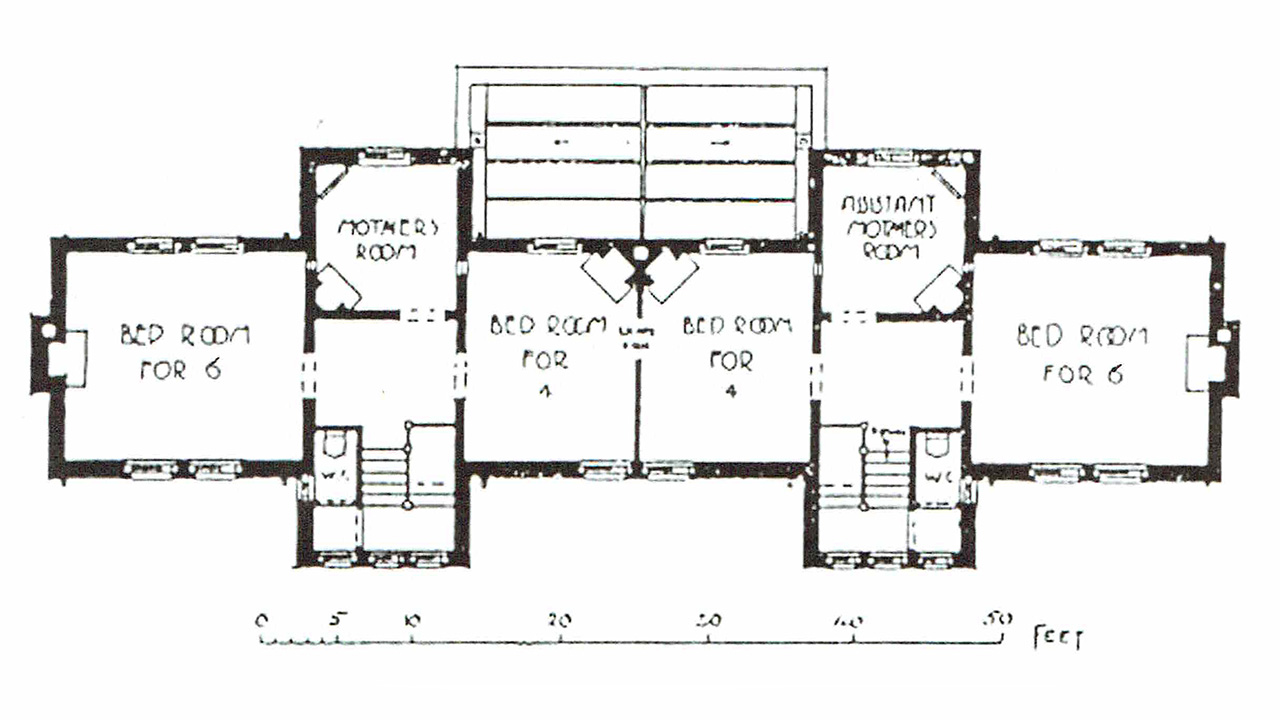

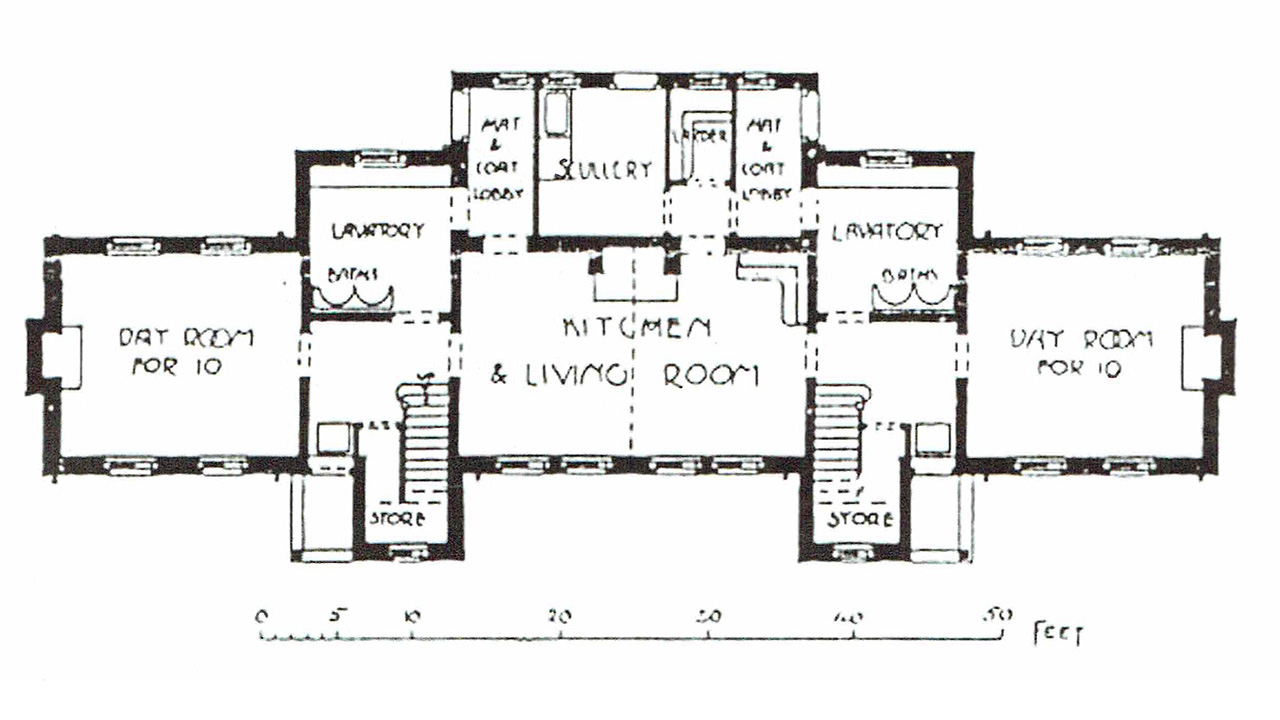

The original plan provided a communal kitchen and dining room. As the number of children were to be in the region of 300 it was decided that it would be better to provide each cottage with its own kitchen and dining area by means of a rear extension. This involved the architect, W.A. Finch, in considerable alterations to the drawings, and there were other changes too, including glazed pipes for drainage, and blue bricks on the cottage fronts. Then the weather stepped in. Just before Christmas 1903, the contractor asked for more time to complete, as bad weather and flooding had caused some delay. In February 1904, it was impossible to get on the site as conditions were so bad.

The weather improved in the spring, but there were new problems. The tenant farmer, Mr Pratt, who had permission to crop the land while building proceeded, complained about poaching on the site. A search revealed six wire snares, and the finger of suspicion was pointed at the workmen. The poaching stopped. Another boiler was found to be necessary as the original could not get hot water to the second floor. In October 1904 the board decided that the building should be lit by electricity at an annual estimated costs of £604, 8s 0d. A generating plant was to be installed together with a 10 tonne Weybridge at the porter’s lodge. The contractor pointed out that this would save the cost of cutting out the walls to take the gas pipes for lighting. Autumn also saw problems with the toilets and the bathroom flooring.

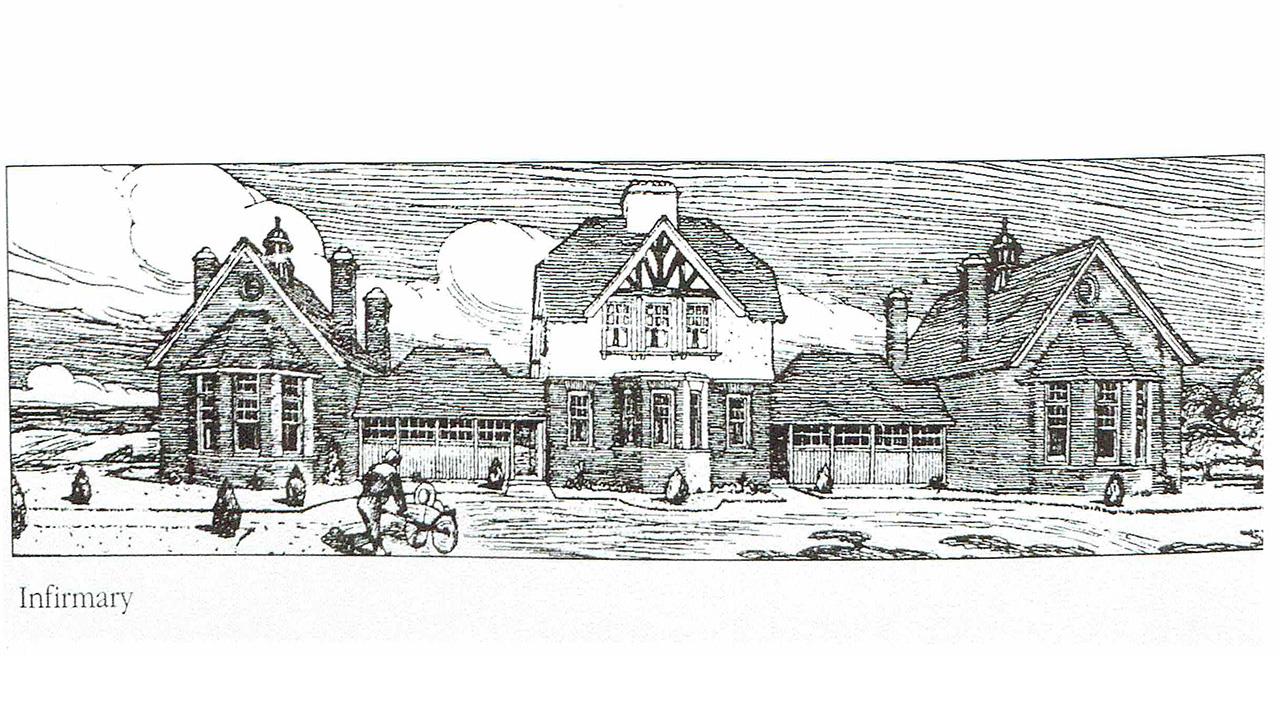

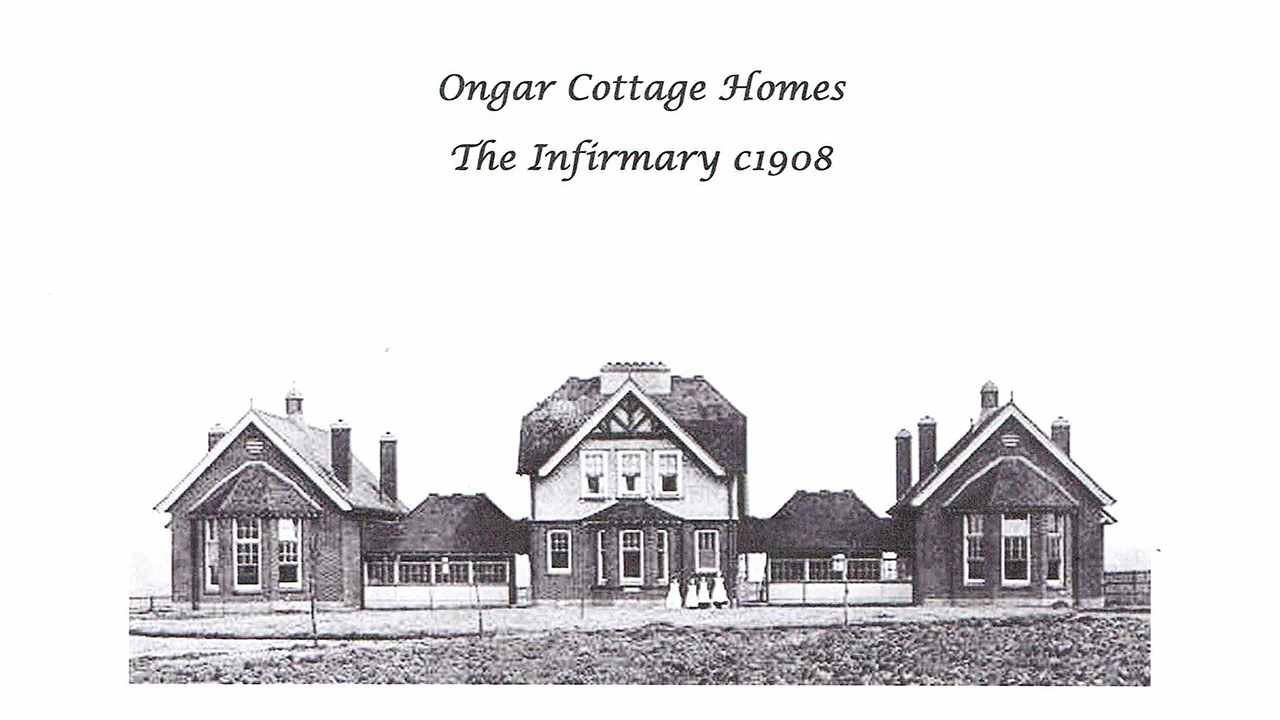

Messrs McCormick must have been glad to have seen the end of 1904. However, things did not improve. In the new year the Infirmary was struck by lightning and had to be partly rebuilt. Then one of the board members, who was not in favour of electricity, put an amendment to the committee in favour of gas lighting. After considerable debate, this was approved, though McCormick pointed out that this would increase the cost as the walls would have to be hacked out to put the pipes in.

The board then instructed the builder to fix the gas pipes on the surface of the walls! It also decided to provide a laundry capable of dealing with 4000 to 5000 articles of clothing a week and approved the additional cost of £1,500.

Completion at last

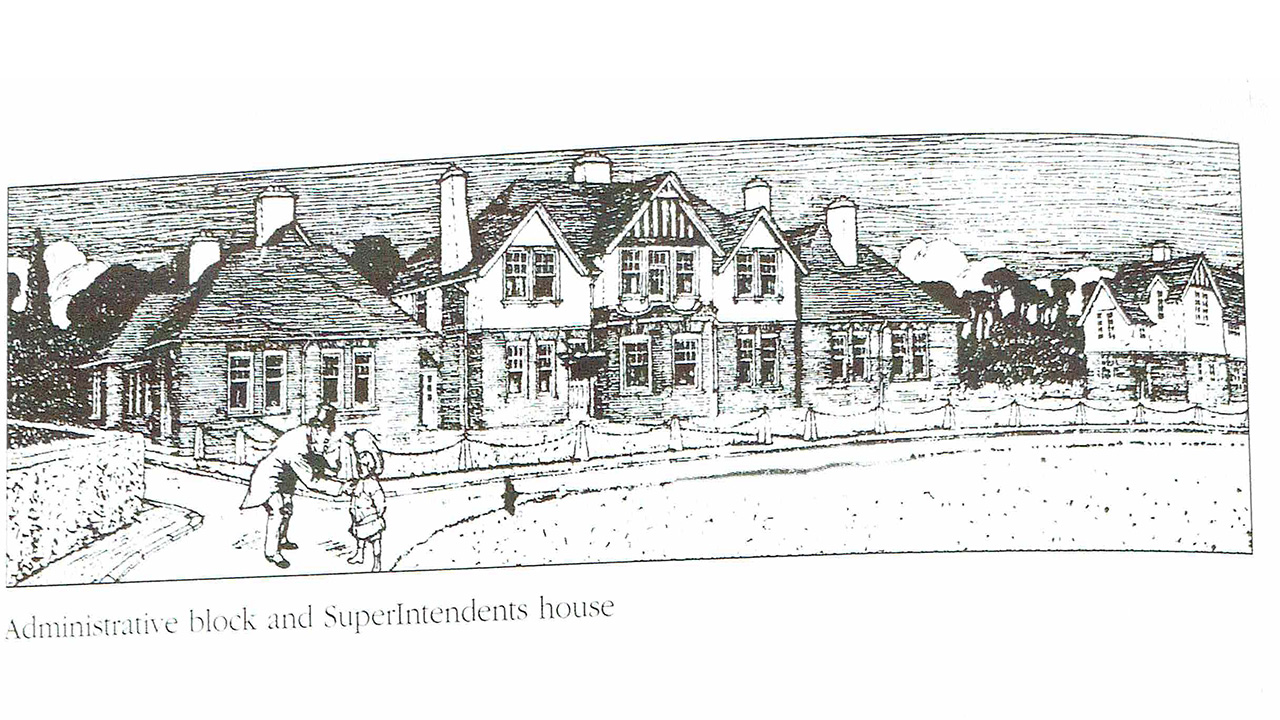

Messrs McCormick handed the buildings over on the 6th of November 1905. It had been decided that the houses should be named after members of the Hackney board of guardians. Starting from the administration house to be called (Fenton Jones house) they were to be named Howlett, Weston, Russell Morley, Carlisle, Warick, Shaftesbury, May and the Hospital. A month before the handover, the guardians had accepted the lowest tender for the school building, being £6987 from F.E Davey Ltd of Southend. Contrary to their previous decision to educate the children in the cottages, it was decided to leave the buildings empty until the school buildings were completed. As there is no central heating, a caretaker was employed to light and maintain fires in the houses in order to keep the buildings dry. After some time, he complained that he could not keep up with the task, as by the time he had dealt with the last fire, the first one had gone out! He was given an assistant who was paid £1 per week. Nevertheless, the buildings deteriorated in the three years that they were empty and all the ceilings in the large rooms had to be hacked out and replastered. During this time, objections have been raised about the naming of the houses and on the 28th of September 1908, it was decided that they should be renamed after the tree planted in front of each building.

Preparing for the intake

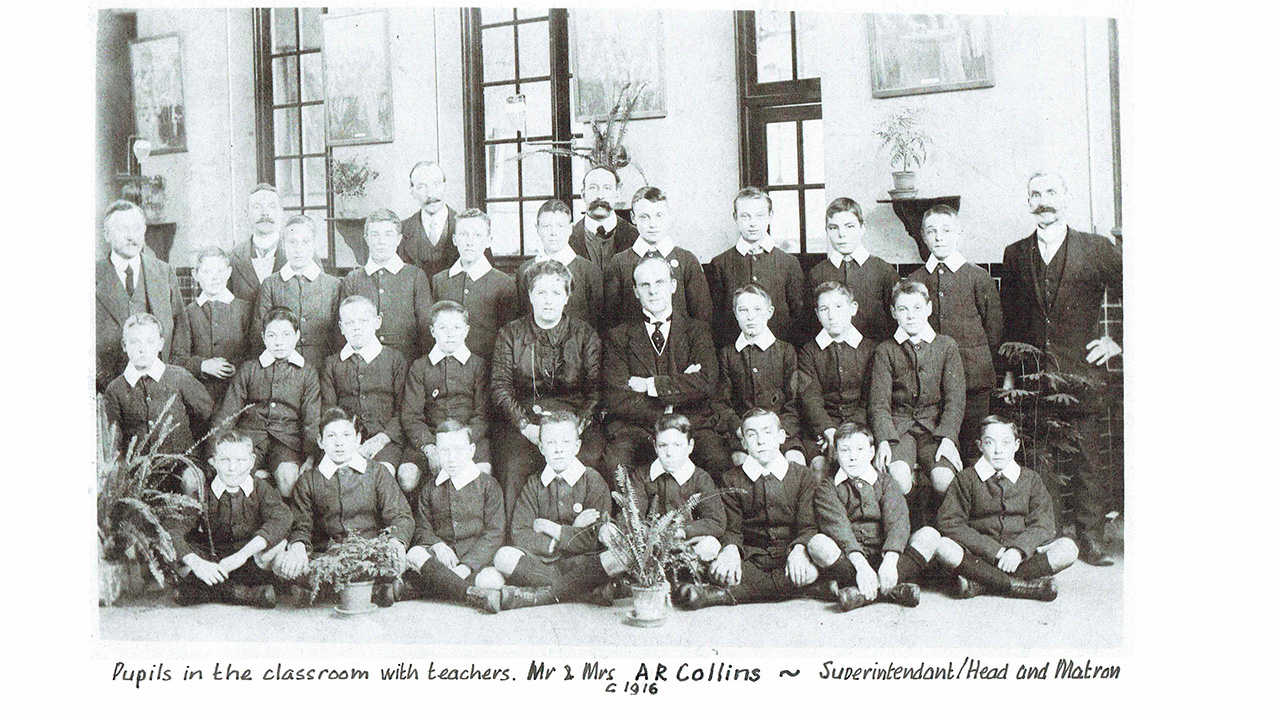

Before the completion of the school, it had been agreed to appoint Mr Spencer from the Brentwood school as superintendent/head schoolmaster at a salary of £150 per annum, with a biannual rise of £10 to a maximum of £180. His wife was appointed as the matron and would receive £40 per annum, rising in £5 increments to a maximum of £60. With their two children, they were also to have full board and laundry. Recruitment of other staff followed, and naturally teachers from the Brentwood school were anxious to transfer to this lovely new environment. Five were successful, followed by the clerk and storekeeper. Other appointments included a specialist teacher in drill, drawing and music (at £90 per annum), assistant matron, porters, engineers, stokers, night watchman, two needlewomen, 3 laundrymaids, an ironer and helper, bandmaster, carpenter, plumber, gardeners, tailor, shoemender and 21 foster parents. Many Ongar families found jobs in the new home, one such notable being Flo Ethel Bolden. As senior laundry woman, she turned the laundry into a small business, taken in washing from several other Hackney establishments. By October 1908, all 114 staff had been appointed and the first children were admitted from Brentwood on the 12th of November 1908.

Inevitably questions asked about £8,550 overspend. After numerous visits by the guardians and government officials, it was agreed that the costs were justified. The result was well designed home in open country, with plenty of open space for its 300 children, with 126 of them being educated in its own school. All the members of the Hackney Board of Guardians were pleased with the result of the eight years’ work. The unsuitable Brentwood school could now be closed, and consideration given to building a more suitable replacement. The guardian's original intention was for the home to provide accommodation and education only, but it was reported that in the first two years 90% of leavers ended up in the workhouse. The guardians did not want the home to become a workhouse feeder. Therefore the various tradesmen who had already been employed were upgraded to become instructors, and by 1910 the leavers were trained for a trade and all found work. Ironically, as education was not considered important for girls, it had always been the intention for them to be trained for service. The superintendent’s wife kept a watch full eye on several in her own home.

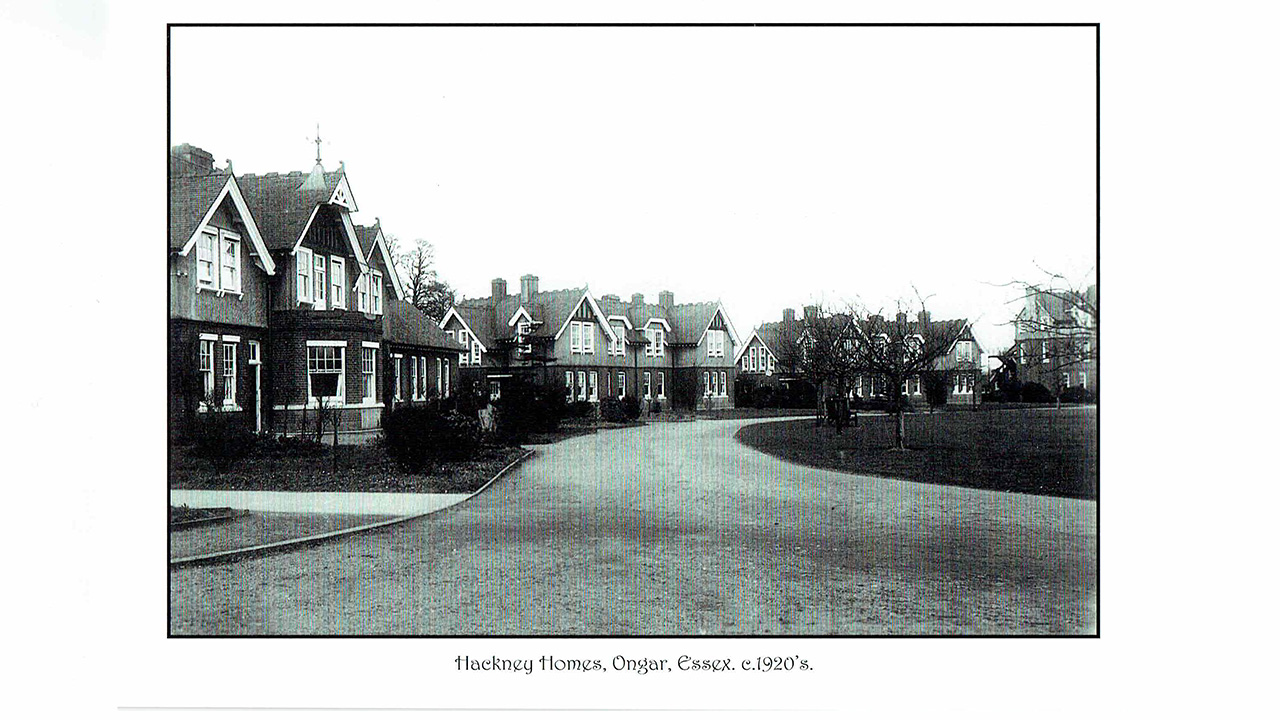

The children who were transferred must have been overjoyed to be removed from such crowded and outdated conditions. The new Hackney Homes (as they came to be called) must have seemed heavenly. Ongar itself benefited too, both from the new jobs and from the new houses that McCormick had put up for their employees. Some of these in the Fyfield Road were sold to the guardians and were used to accommodate non-residential staff.

Has the pendulum swung too far?

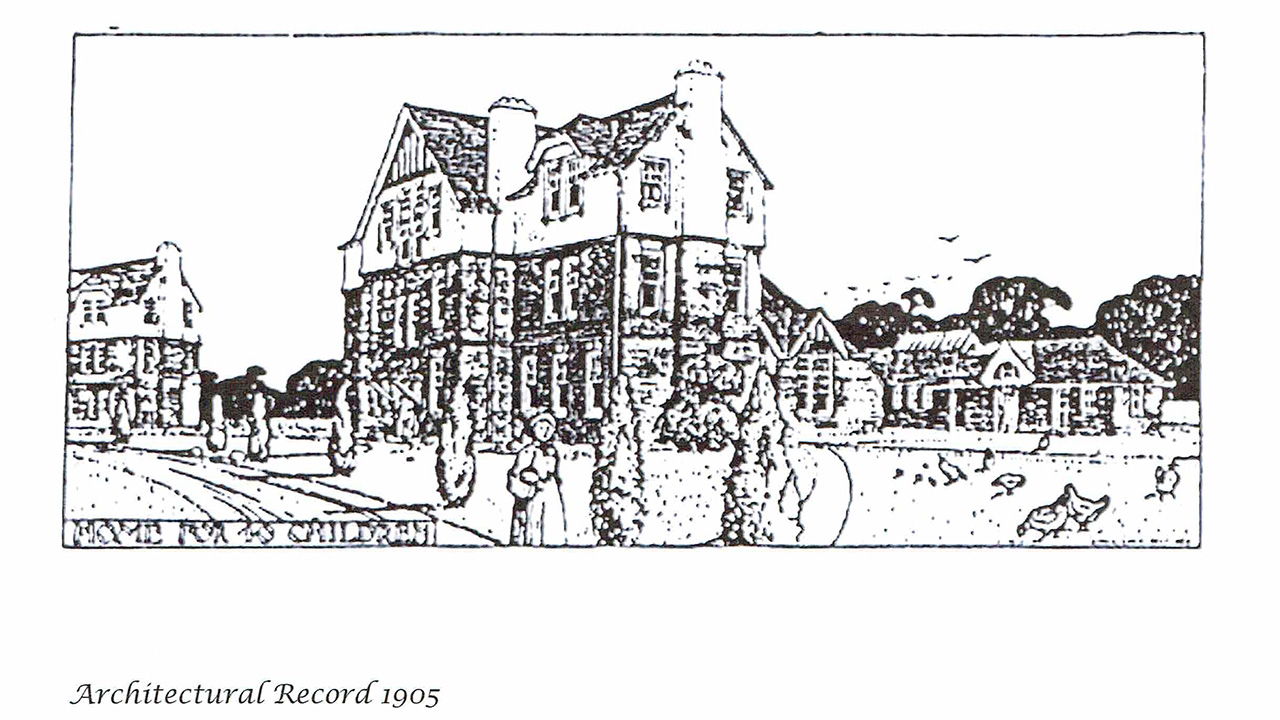

Not everyone was happy with the result. A descriptive article appeared in The Builders Journal and Architectural Record of 29th of March 1905, some eight months before completion. It stated ‘the children's colony of the Hackney Guardians in the quiet little town of chipping Ongar in Essex, shows that so far as creature comforts are concerned, the lot of the workhouse child is not devoid of its advantages. It is indeed a question whether in the revulsion from the former severity with which Boards of Guardians were wont to regard their hapless charges, they have not allowed solicitude for their welfare to urge the pendulum unduly in the other direction.’ It then went on to criticise the size of the cottages, designed to house 40 children each, ‘as being prejudicial to the cottage character of these buildings’ and expressed the view that they should have been limited to two storeys in height. The writer seems to have been rather out of touch with the enormous problems facing the guardians, who had 800 children in care, many in very overcrowded and prison-like accommodation, with 100 children under the care of one officer. Those who returned later, to show their own children where they had grown up, never spoke about being overcrowded. Later in the century, with changing requirements, the numbers were reduced. By 1964 the cottages accommodated 30 and in the 1970s fire regulations reduced the number to 20.

It was the only home I knew

For 22 years these buildings were home to the poor part and foundling children of Hackney. The author instituted an annual reunion in the 1970s, and the elderly attenders spoke well at their time Ongar where they were well fed, well clothed, and well looked after. For many it was the only home that they could remember, as their early years were so traumatic. During their stay they had been reminded how lucky they were, and how grateful they should be to the wonderful board of guardians. Girls were instructed to curtsy to visitors looking around while the boys had to doff their hats. They all learnt a trade before they left so that they would not follow their parents into the workhouse. Fruit and vegetables were grown in the garden to reduce costs, any surplus being sold to other Hackney establishments. Much of the children's clothing was made or altered in the sewing room. The sewing ladies, assisted by the girls in training, saw to all the curtains, bedding and so forth. Both boys and girls were trained as tailors, and many lads learned how to make shoes. It is ironical that by taking these children away from their impoverished families, mothers were often able to go out to work to supplement the family income. There is nothing new about counter-productive social policies!

The end of the poor law

The act of 1929 ceased the funding of the Poor Law system, and a survey of all children’s homes was undertaken. Concern was expressed about the poor fire escape facilities at Ongar, that the roads and pavements were cracking an in need of repair and at the school needed more room. Times were changing and the Ongar Homes had seen their best years. The buildings, and the responsibility for the children, passed to the London County Council on the 1st of April 1930. The Ongar Cottage Homes were now called the Ongar Residential (Public Assistance) School. Nine years later the school closed and was re-opened by the London County Education Committee as a residential school for boys with mental health issues under part 5 of the 1921 Education Act. The new head was Mr W. Uden, transferred from a similar school in Acres Lane, Brixton, on a salary of £546 per annum. Mrs Uden was appointed matron. During the war years many of the boys were evacuees. After the war, Bowes Farm, on the other side of the road, was purchased for £5,650 for the housing and training of the more difficult boys.

Mr and Mrs Uden retired in 1956 and were replaced his head and matron by Mr and Mrs Stanard from a London School for deaf children. By this time, the name ‘residential school’ was not felt to be correct and there was a staff competition to suggest alternatives. After some deliberation, the name Great Stony School was adopted. The Stanards retired after eight years and Mr R. Barnes was appointed headmaster in 1963, taking up the post on the 1st of April 1964. The matron was Miss Deacon, Mrs Barnes not wishing to be appointed as she was more interested in teaching. Mr and Mrs Barnes were rather surprised on their arrival to find three maids at their disposal, as well as the fact that the main gates were locked at 10:00pm! The maids were quickly re-deployed and the gates removed.

Soon after, the Education Department was separated from the London County Council and became the Inner London Education Authority. In the early 1990s, with the abolition of the Greater London Council (which was the successor of the LCC) Great Stony School was returned to the borough of Hackney and the circle was complete.

The end of the school and a new beginning

Mr Barnes retired in August 1988. With the threat of closure hanging over the school, Mr Clive Tombs was appointed in his place. The intention was to close the school as soon as the ILEA was wound up, but the government would not allow this and insisted that it should be returned to the Borough of Hackney. Initially Hackney refused but changed its mind on being reassured that they would be allowed to sell the property. The campaign to keep the school open was doomed from this point and there was a steady drop in pupil intake until the school was not an economic proposition. Closure inevitably followed and the buildings remained empty for several years apart from their use in filming ‘The Clockwork Mice’ in the summer of 1995. Hackney sold the site to Taywood Homes in September 1997 and at the time of writing, the builders are struggling with a particularly wet winter to convert the cottages into luxury homes for sale.

The End.

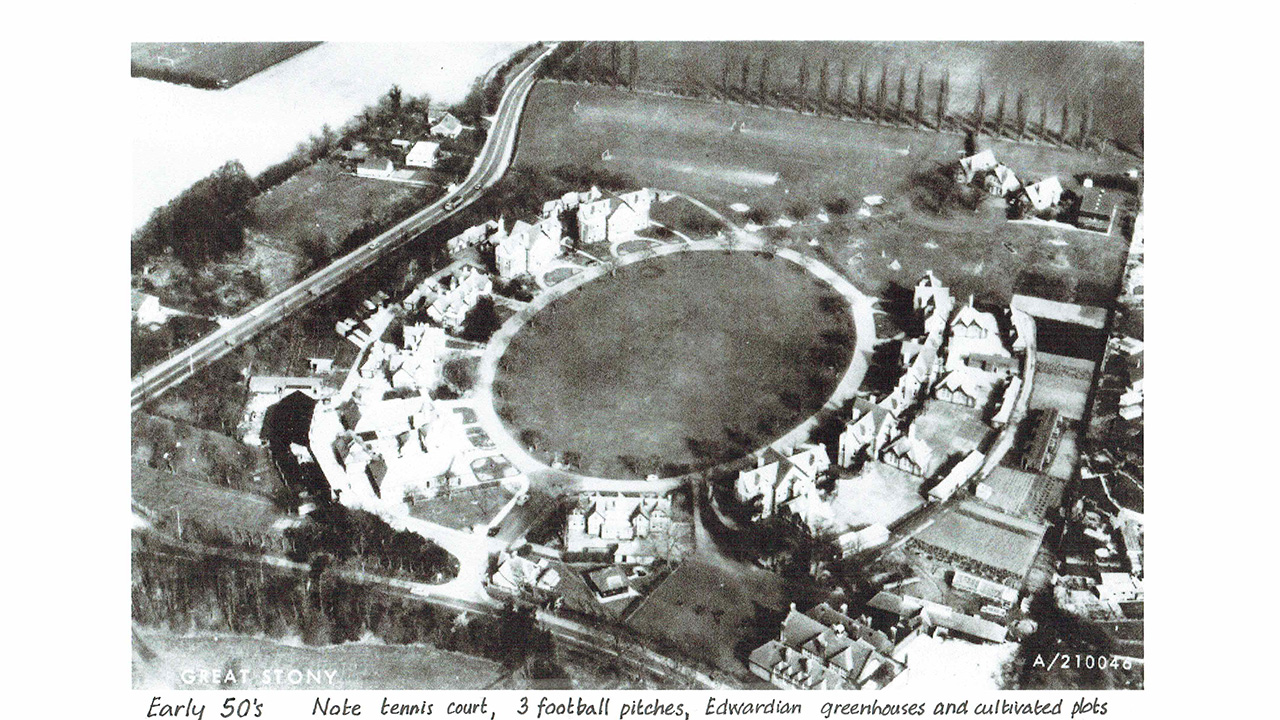

More related images can be seen in the Great Stony Park Historical Gallery

More general information about Hackney Cottage Homes can be seen on this external site: http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Hackney/homes.shtml. Please note some pictures may contain an image of your house taken very much after the estate was private. We are not sure who gave the photographer permission to enter the site and take those photographs but it is nothing to do with GSPRA Ltd.